Counselling can be for anyone.

It is interesting how counselling is associated with mental ill health. Nick Clegg at the Liberal Democrats conference (2014) promised to increase spending on mental health, and there is frequent debate about putting mental health spending on a parity with that of physical health. I however, am not debating whether your mental health is sub-optimal and you ‘need’ treatment, I am proposing that just like we indulge our body, we should perhaps be a little more attentive to our mind/soul/spirituality.

I could google the cost of a spa break, or how much we spend on wasted gym membership. Or I could start on the cost of teeth whitening, facials, liposuction, a touch of Botox, these are accepted behaviours, which incidentally, are not inexpensive, that are used to help us ‘feel good’ about ourselves. Behaviours which we do regularly and then need to do them more frequently for the same benefit and then up-grade, and repeat the cycle.

We attend to the body, the shell, our physical form. This is how we see ourselves in the mirror, and it is important. Our acceptance of this picture in the mirror, is often conditioned by a view that society gives us regarding what is aesthetically pleasing. Some of us our more bound by this view than others, and constantly need to pay attention to how we look in order to feel ‘acceptable’ and ‘accepted’ to others and ourselves.

I recently was introduced a group ‘Health at Every Size’ one article caught my eye, Weight Science: Evaluating the Evidence for a Paradigm Shift . This article demonstrates how powerful non-health based influencers have been on defining what a ‘healthy weight’ is. This has not been challenged enough by scientists and health professionals.

The general dissatisfaction of our ‘form’ that many of us have is not a ‘mental illness’ and yet it impacts on our relationships, our ability to get satisfaction from social events, our enjoyment of holidays, because it results in us carrying an anxiety about how we see ourselves and also how others see us.

Then there are those of us who despite having a good quality of life, the family we aspired to, the regular work promotions good physical health who feel guilty that despite this they do not feel satisfied/happy. We wonder ‘what is the point’. This is not ‘mental illness’ yet impacts on our relationships our potential to do well, and our overall enjoyment of what we have.

Another group of us carry a sadness (which may be experienced as anger or frustration), it is associated with an aspect of the world, people, society, animal or human welfare, our environment, things that are ‘not good’, for example war, pollution, famine, global warming. Often we have little control of this as an individual but feel as a race/ species uniting we can have greater influence, so endeavour to put energy into this. This sadness can be overwhelming, it has a moral or ethical feeling and is hard to ignore. This is not a ‘mental illness’ yet impacts on our relationships, and our satisfaction with our own life journey.

These issues can slip from being motivators to de-motivators, we may feel like a failure, or unlovable, or even worthless, or insignificant. Not a mental health problem, but nevertheless leads to low mood.

Many of us with strong social networks, good communication skills, and who trust those that love us and are close to us, can share these doubts well enough to grow through them and understand themselves better.

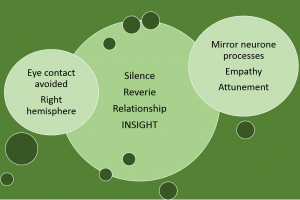

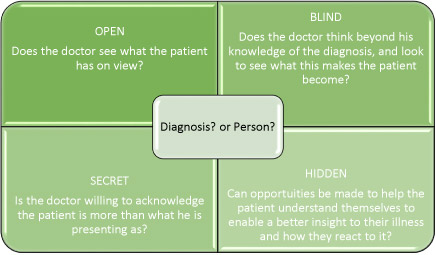

Those that are not so fortunate may find their support through counselling. Counselling provides an unconditional space to explore what is that makes us who we are, counsellors generally believe that we are all ok, exploring the things we don’t like about ourselves can be done safely and without fear of judgment. Allowing reflection and opportunity to see things from a fresh perspective.

The benefit of doing this is often felt immediately; having the space to be who we truly are and explore our defences and anxieties in a contained consultation with a stranger who has no vested interest is liberating.

You may even want to try counselling just for the experience!