Eating Disorders- Do you Recognise Physiological Hunger?

Prompted by Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2015

Identifying the motivation behind our eating.

Part 1

An article on ‘Anorexia’ and ‘Bulimia’ this isn’t for me? Stop a minute. This is not about these conditions. Both Anorexia Nervosa (AN) and Bulimia Nervosa (BN) are familiar terms to describe mental distress that has manifested as an altered eating pattern. They tend to be diagnosed when the eating habits cause physical symptoms. Unfortunately this is often years after the illness first started. The symptoms associated with AN and BN can also be attributed to other conditions delaying accurate diagnosis still more. I want to make readers aware that unhelpful eating behaviours can be disordered before they manifest in a physical illness. If you want to know more about AN and BN visit Beat Eating Disorders or Eating Disorder Help where some really useful information and support can be found.

6.4% of adults display signs of an eating disorder. I hope this blog raises awareness of eating habits and how they become unhelpful and the lack of trust we have in ourselves.

Many parents will be vigilant towards their children, especially daughters, watching for signs of dieting, over eating, missing meals and vomiting, some may be aware of over exercising too. When does this vigilance start? It’s interesting isn’t it? The vigilance regarding what you put into your child’s mouth will start the moment they are born. It happens partly as a result of the monitoring that is done by your well intentioned health visitor, who weighs and checks your baby to see that they are ‘normal’ to check for early signs of failure to grow, really key in spotting childhood illnesses. Do you remember how keen you were to know their opinion, and these results, and how they were interpreted? How much did you pay attention to this information, getting reassurance that little ‘Sammy’ was following the right ‘centile’? Or did you have confidence in yourself that you understood your baby’s needs? I imagine with each child you had your self-confidence grew.

Perhaps it even started earlier, the great debate to breast feed or to bottle feed?

The point I am making is that from our start in life there are external influences for example; societal, health, cultural, economic and fashion that detract us from our instinct, and heighten our anxiety about what we feed our children. For some this can have an influence on our relationship with food, body image and eating habits. For others it may manifest as ‘keeping up with the Jones’. Reassurance and a sense of belonging; being ‘normal’ is very important to us. Below I demonstrate that when we are children, dependent on others, food can be attributed qualities that are not real. It is these qualities that may contribute to an impaired ability, for us as adults to eat instinctively.

Two common examples that can become deeply imbedded in our unconscious are;

- Food as a prize

This emotional labelling of food may start very early, the weaning infant given a ‘treat’ for eating something we as the adult perceived as not nice. Little Sammy finished the browny-green looking sludge that was a ‘casserole’, carer smiles and looks happy, and then gives Sammy something that excites (or over stimulates) his taste buds. Sammy is stimulated emotionally, seeing his carer happy and this is rewarded by sensory stimulation, in this case taste (a fix).

In isolation this is quite normal, it’s when emotional stimulation are void in other situations. Seeing a carer happy when Sammy does other things, experimenting with touch, walking, playing, etc. will provide a balance. Sammy will get a sense that many things can please the people around him.

The lesson that is unconsciously learnt is ‘If I eat my food I get something really tasty and then those that look after me are happy’

The potential unhelpful lesson is ‘If I eat all my food, I get more nice things to eat and make the people I love happy and pay attention to me’ or ‘foods that are really tasty give me an emotional fix’. Emotional fulfilment over rides physiological need. Food can be eaten even when we are not hungry.

- Food as a weapon

Little Sammy is still being weaned. Carer is not able to focus on little Sammy, they have so much other stuff to do. Sammy isn’t sure what is expected. He might eat some sludgy casserole, he might feel it in his hands, rub it over everything, and spit it out, all such fun. Unfortunately all busy carer sees is a mess. The carer starts to engage with Sammy, they might be cross, or just chatting, but she is at least engaged, and not ‘busy’ elsewhere. Sammy responds to this engagement and it is good. The lesson Sammy learns is ‘at meal times my carer is busy, I need to do lots of stuff to get her attention’

Unconsciously this can manifest as ‘I can use food to manipulate people to pay attention to me’

These examples describe how food can be used, unconsciously, not as a fuel to keep our body nourished, but as an emotional tool to get something we want, to feed an emotion. Clearly we all were exposed to these types of scenarios as infants, and are not all affected by unhelpful eating habits as adults. But those that find themselves yoyo dieting, eating in times of stress, or happiness or during relationship breakdowns may well be drawing on childhood experiences that had historically been useful and provided emotional satisfaction.

To help understand the concerns you might have with your own eating behaviours it is useful to take a step back and focus on becoming attuned to what is going on for you when you eat both emotionally and physically.

If you have practiced mindfulness or other relaxation techniques, you may find them helpful.

For a day or 2 each week, or more if you find it really useful, try to focus on these questions EVERY time you eat.

On these days, before you eat spend a minute or two deep breathing and focusing on something simple, such as your breath going in and out.

Ask yourself

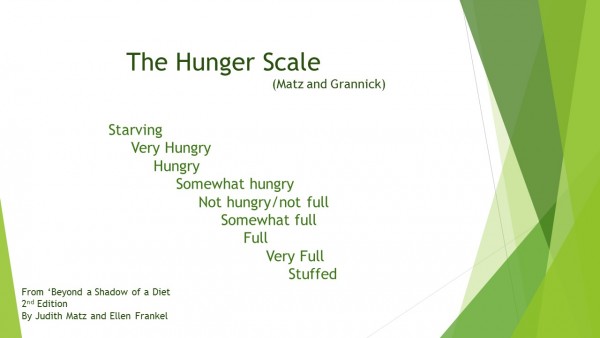

- Where you are on the Hunger Scale?

- Why am I eating?

- Because I am at an appropriate place on the hunger scale, and feel physiological symptoms of hunger

- And/or Because it is a meal time/ a meal is to be eaten

- If you are eating because it is a meal time, and not because you are hungry reflect on whether you can eat at a different time. Or how necessary is it for you to fit in to meal time.

- I don’t know, I know I want this particular food.

- If this is the case, try identifying where the need comes from. An emptiness somewhere? A desire for a sensation in your mouth which will give you pleasure (a fix) it could be anything.

Having answered these questions, eat and enjoy.

Establishing your motive for eating is useful and the first steps to changing eating habits that you know are not helpful to you.

In part 2 I will describe how this can be developed to help you become attuned to food types and self acceptance.

You may find it interesting to look into Mindful Eating, or Intuitive Eating and the organisation Health at Every Size (HAES)

Some of these ideas evolved from Judith Matz and Ellen Frankel’s book Beyond a Shadow of a Diet.