Health Care Professionals must exhibit true empathy with their ‘over weight’ clients. Judgement and stigmatisation is not helpful.

This blog is a personal reflection of the knowledge I hold regarding obesity and its treatment. Information I have gained as a dietitian and latterly a counsellor. Counsellors generally try to follow three core behaviours; empathy, unconditional positive regard and congruence. It is these that have stimulated my re-evaluation of my beliefs about obesity and created a need for me to hold several positions of understanding all of which contain truths.

It is normal for our understanding of what is true and what is not true to be about facts, and interpretation of data. I see truth as this and more. There is truth in human experience for example. A client sat opposite me, suffering with self-loathing who says;

‘I just start to eat and just cannot stop’

The client is telling me the truth. That is what they experience. Another parallel truth is that the body responds physiologically to satiety and so individuals know when they are full. Both are true simultaneously.

I am going to identify some of the truths that I believe about obesity. This is a blog. These are my educated beliefs.

Personally held truths

EMOTIONAL TRUTHS

When self-acceptance is dominated by the need to conform to external messages we become less attuned, less able, emotionally and physiologically to be who we are.

There is no such thing as a bad food, a diet that is balanced and varied can include a variety of foods. By this I do not mean a daily diet but a diet taken over weeks.

Labelling foods as ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘naughty’, ‘rewards’, ‘treats’, ‘healthy’, unhealthy’, ‘forbidden’, ‘wicked’ is unhelpful, and potentially damaging.

We are a complicated animal, our physiological development runs parallel to our emotional one. Issues of self-esteem, self-worth, identity, recognition are all developing as we grow. In families it is common to create an emotional meaning to food, either knowingly or not and this becomes imbedded in our emotional responses as adults.

A simplified example might be the use of sweets as a reward. Because sweets (chocolate, biscuits, cake etc) may not be freely available to a child and are associated with being good a child will become less able to control their consumption using physiological markers and more likely to be influenced by emotional markers. The absence of sweets therefore being associated with negative emotion and their presence a reward. So as an adult in low mood, it is logical to make oneself feel better by giving oneself a reward, (of sweets) just as their parents would, irrespective of hunger.

‘Finish you meal’ A young child (age 1-3 ) eating to appetite-(i.e. using physiological cues) may leave food on his plate. A parent, for one of many reasons does not want this. The child who is also learning about the affect his responses have on receiving attention from his care-giver, is encouraged to finish his plate. Instead of affirmation that he knows when his body is satiated (i.e. allowed to leave food) he is encouraged to over-ride this by finishing his meal in order to get affirmation from another. He is being taught how food can manipulate others, and/or that finishing food beyond satiety pleases those he cares about. These messages become embedded and may not even be part of our conscious decision making by the time we come to adulthood.

These are two simplified examples of what might go on in childhood that has a profound affect of appetite control in adulthood. Instead of labelling them as greed and lack of self –control, perhaps HCPs think of these as examples of self-soothing, or self-affirming behaviours.

Knowledge of food and good nutrition is empowering

- Mothers-It is our mothers, or primary care providers, who significantly influence our food choices throughout life. A mother with an adequate knowledge of nutrition and meal planning will provide experiences and habits that are reinforced throughout childhood

- School- The curriculum can teach children about health, and this can be reinforced by the provision of appropriate food in the school environment.

- Families-Awareness of cross-generation food preferences provides opportunity to create and sustain a varied diet, incorporating a variety of foods and cooking methods.

- Ill health- Often this provides a motivator to be curious about optimising health, empowering individuals to take control of health, exercise and diet

- Work place-Reinforcement of positive food choices

- Public Health messages-By which I mean consistent, easily accessible information- for those who want to learn, feel able to change, are literate and motivated. Is an useful way to advice on evidence based dietary guidelines.

The regular supply of a varied diet throughout the life cycle without recourse to bribery or reward, would greatly enhance the normalising of food.

Lack of knowledge does not directly cause obesity

It would be paradoxical to believe the body is able to control energy intake and also believe individuals are not able to control their intake through lack of knowledge of nutrition.

Energy balance

Individuals gain weight if they consume more energy than their body requires over a long period of time

Energy intake =Energy output=Weight maintenance

Physiologically control

There are ways in which the body has evolved to control energy intake. These include muscle receptors along the gastrointestinal tract, secretion of regulatory hormones, nerve stimulation and brain involvement and several endocrine functions.

Breast feeding- There is a link between breast fed infants and decreased incidence of obesity. I believe the cause is multi-factorial, some factors being:

- Demand feeding-The infant demonstrates an ability to react to hunger and satiety

- The infants success at being fed to appetite is positively reinforced-the infant ‘learns’ to trust his body.

- The mother responds at a physiological level to provide the necessary nutrients

- The mother responds at an emotional level to positively reinforce that she is able to respond to the infants needs timely and appropriately. The supply of food is met without creating emotional stress or anxiety from either infant or mother.

- The composition of breast milk is appropriate for the growing infant.

Other factors that inhibit or prevent or disguise our ability to control physiologically our energy balance.

External factors

- The food industry-Expansive food choice, manufacturing methods, marketing, additives-colour, flavour, and preservatives all these and more serve to stimulate desire for foods outwith physiological need.

- The glamour industry-How an idealised body shape, both for men and women detracts from the beautiful array of healthy shapes and sizes that men and women naturally have, these become unacceptable especially to those with low self-esteem and self-worth. We only need to look at other cultures and through history to appreciate how our interpretation of a ‘beautiful’ shape and sized body is a societal concept not a health one.

- The health industry- Obesity has become a disease measured by a scale created for insurance purposes. It has made the assumption that there is a direct correlation with weight and health for all resulting in the belief all people with a BMI (for example) of 27 are equally as ‘unhealthy’. This belief is rarely challenged.

So what?

There will be individuals, physically fit and healthy with a BMI of 27, a proportion will have low self-esteem, a poor sense of self-worth, and generally not feel good about their size- (after all society teaches them it is ‘bad’). Assuming they can actually control their weight perfectly adequately using physiological markers, there self-worth is undermined by external factors and they begin dieting. They are told they are unhealthy! Foods that were once enjoyed and managed become ‘naughty, bad, denied’ and then craved. Their weight yoyos. Ironically it is this yo-yoing in weight that is more harmful than obesity per se. So the diet industry and our obsession with the perfect form and an inappropriate non-reflective use of BMI as a measure of health have made low self esteem into an obesity problem.

Just this month (Jan 2015) research from Cambridge has provided evidence that inactivity is more significant than obesity in increasing mortality rates. http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/lack-of-exercise-responsible-for-twice-as-many-deaths-as-obesity

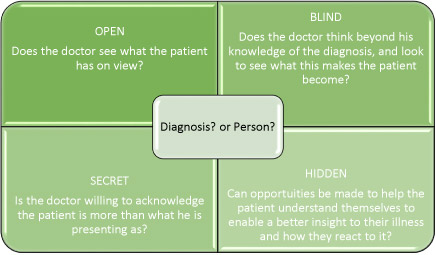

As a counsellor and dietitian my approach to clients who want to change their eating habits, is to first help them love and honour themselves. In time, with support and empathic challenging their emotional hunger will not need to be satisfied by diet, and their self-esteem not affected by inappropriate stereotypes.

The weight loss industry should perhaps begin to feel some responsibility for its perpetuation of the false idea that obesity is self-inflicted, and begin to offer empathy and positive regard for those it serves.

I endorse regular activity and a varied balanced diet as a means to good health.