Christmas Stress-How to change your mindset using Mindfulness

Christmas Stress – How to change your mindset at Christmas

Anyone hosting Christmas will be aware of all the jobs that need to be done, the presents and party clothes to buy, food to be ordered, the list can go on. For those having Christmas alone, or if this year is the first without a loved one, the festivities provide a complex set of emotions which can be difficult to bare.

It may be that you have a silent dread of Christmas. However, Christmas is going to happen.

What follows are a few ideas about how changing your mindset may help.

Many of the reasons why stress builds up prior to Christmas is to do with thoughts and behaviours, habits and expectations.

For example;

- The emphasis placed on family traditions

- You may be concerned about how much work needs to be done to make the day successful

- Present buying; how much to spend, what to buy

- The day being a reminder of those we have lost

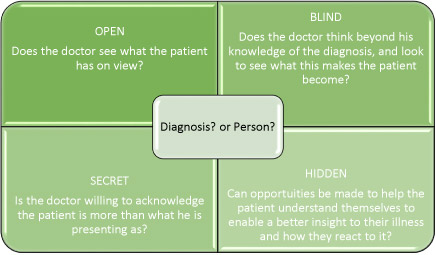

You may be able to relate to these. Mindfulness encourages a different approach and awareness to the meanings we give to things such as traditions and expectations.

Mindfulness allows us to treat the current moment as all there is. It helps us see how much meaning we attach to the past at the expense of the present.

- The emphasis placed on family traditions

It can be difficult to change habits, certainly if we frame them as ‘family traditions’. I wonder if when your ‘family tradition’ happened for the first time the intention was for it to go on past its sell by date?

Interestingly we are aware in other circumstances, such as holidays, that when we try to repeat the experience it causes greater disappointment. Can this be applied to Christmas?

Traditions may include when to put the decorations up, real tree or artificial, Christmas day menu, the family members invited, the timing of present opening, television and what film to watch.

Before planning gets well under way why not ask yourself and your family, whether these traditions important and why. Do they create a good experience?

You may find you can drop one or two and everyone has a sense of relief.

- The concern about how much work needs to be done for the day to be successful

There is as much work as you want. Is it true that the more work you put in, the happier everyone is? Or is this about you, and how others might perceive you?

Thoughts can creep into our head and be believed. At Christmas there might be a little bit more organising and planning but it happens every year and we do it every year. It is often worth noticing the thoughts we have, and reminding ourselves they are thoughts. There might be the thought, ‘I won’t get it done in time’ or ‘what if the turkey is under cooked ?’ Notice what happens to your stress levels when you have these thoughts. Are they appropriate, what is the worst that can happen? Thoughts are not facts, mindfulness enables us to notice a thought and not react to it.

Take a mindful moment. Take a deep in-breath and a slower out breath, counting to five. Repeat once or twice more.

- Present buying; how much to spend, what to buy

Why are you buying presents, who for and at what cost?

Present buying is a reflection of who you are and your relationship with the recipient, as well as your personal beliefs about Christmas.

There are many ways in which we get distracted from this, especially adverts and consumerism and ‘family traditions’. The shops become full of ‘gift ideas’. Spend a little time reflecting on why you want to give as a gift. There is some truth in the statement ‘it is the thought that counts’. A mindful approach focuses your mind on the reality of Christmas, encourages you to stick to intentions meaning it is less likely you buy things spontaneously.

You may also reflect on what does receiving a gift mean to you, and is this truth based on reality. A common belief is that a person close to you will instinctively know what you want. Unfortunately, life isn’t this simple, either tell them or be prepared for anything. People are not mind readers.

- The day is a reminder of those we have lost

Anniversaries are reminders. Allowing a time in the day to acknowledge absent friends and family can be useful. You and other friends and family also represent a little of that missing person, a shared joke, or shared gene, this too can be honoured. They have not gone completely.

Mindfulness encourages us to stay in the here and now, it is this moment that is important, comparisons often bring dissatisfaction. Each Christmas will be different, enjoying it for what it is can be more rewarding than not liking it for what it isn’t.

Mindfulness at Christmas

Mindfulness involves a regular commitment to paying attention to the present moment. Christmas often draws us into the past, the past has gone, enjoy the ‘now’ as this too will soon be gone.

You might be interested in

Thoughts and Anxiety-Using psychotherapy to alleviate stress

Mindfulness meditation for novices-Part 3

If Christmas does provide a challenge getting some counselling support may just help build up resilience.