Thoughts and Anxiety -Using Psychotherapy and Mindfulness to alleviate fretful thinking

Thoughts and Anxiety

Anxiety often manifests itself as poor eating, irritability due to poor sleep, and an inability to concentrate. First line treatment addresses these manifestations. Anxious people are encouraged to exercise to become physically tired; eat regular meals and to make lists to feel less over- whelmed. These are useful for symptom alleviation but without identifying the cause there is potential for anxiety to continue. The link between thoughts and anxiety is not being addressed in these treatment. It is understanding the cause that will ultimately decrease the symptoms of anxiety.

Anxiety might be interpreted as a reaction to a real situation. Do you believe anxiety is a reaction to a real situation?

Have you ever considered your thoughts and anxiety as one problem?

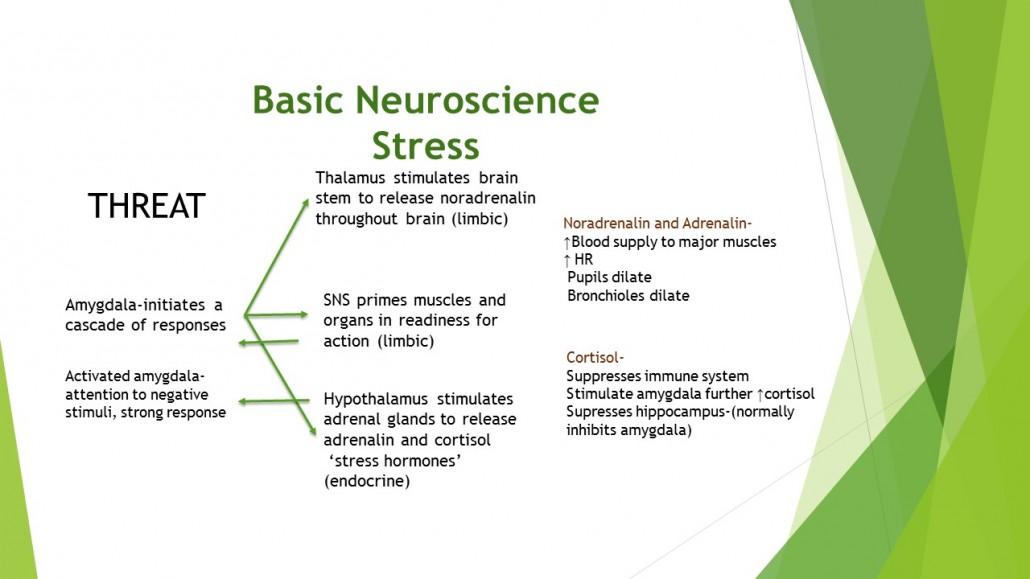

The Neuroscience of Anxiety

The stress response is the same whether there is a real threat to our physical safety or a perceived one. An area in our brain called the amygdala is the warning bell that makes us physically alert through a cascade of hormone and nervous reactions. One of the hormones released is cortisol, which further alarms the amygdala so it becomes even more alert to negative stimuli. Meanwhile, another area of the brain, the hippocampus, becomes less responsive. The hippocampus normally provides a control over the amygdala such that positive experiences are noticed as well as the negative ones and we can weigh up rationally what is the best action to take. The more often we are stimulated by anxious reactive thoughts the more readily we get to a state of alertness and vigilance, and less able to keep calm and rational. We attune into (implicit) memories that are not quite clear ‘the sense of something bad going to happen’; thoughts and reality become inseparable, we become less able to access reality, which might appropriately be remembered as as ‘when such and such happened, I was concerned but it all worked out in the end’.

Thoughts

Thoughts and Mindfulness

In the context of Mindfulness there are 3 types of thinking

- Active-Useful, essential for planning, doing, reaching our goals

- Flow-thoughts occur but are not judged, they pass by.

- Fixed-unhelpful patterns of thinking, not usually based on reality.

Mindfulness aims to help us move away from fixed thinking to flow thinking and active thinking.

It is useful to remember that

- Thoughts are not facts

- We are not our thoughts

We are then in a better position not to let thoughts and anxiety dominate our thinking and behaviour.

A useful way to notice whether a thought is an unhelpful one is whether it creates an emotion, or whether it is helping or not, that is enabling you to do a task or stopping you from doing a task by relating to the past or the future, rather than the present.

Psychotherapy and Thought

Psychotherapy is about understand the workings of the mind, and bringing it into awareness. It is about recognising behaviours that are based on past experiences, and understanding that we do not need to repeat behaviours and thoughts, especially those that cause unhappiness.

The implicit memories that were mentioned earlier, it is these that psychotherapy can help unravel and challenge.

An example

As we grow up we often maintain the beliefs, behaviours and thinking patterns that were familiar to us as children, when they are out of awareness, as adults they can prove to be unhelpful. An innocuous example might be that as a child ‘greediness’ was discouraged. So little Billy, to please his mum would take the smallest bun when offered a plate of cakes. As an adult Billy’s wife offers him a plate of buns, obligingly he takes the smallest, not wanting to be disliked for being greedy, Billy’s wife is upset thinking Billy does not like her cooking. There is something in Billy’s wife’s belief, behaviours and thinking that feels rejected if someone doesn’t accept what she offers.

These actions can be so ingrained that we believe them. Billy believes he is greedy if he takes a big bun and his wife believes she is rejected because he didn’t take the biggest one. These are fixed thoughts. The reality of the situation has not been made explicit, spoken about. In a state of anxiety further implicit memories may be stored (remember these are not based on reality). Billy’s implicit memory might be is that he upsets his wife by eating buns, his wife’s that Billy doesn’t like her cooking. A tiny event reaffirming a whole set of thinking and anxiety based on past experiences not relevant in the present.

Through psychotherapy Billy will gain an understanding that perceptions of greediness are individual. He will identify with his own physiological experience about what it is for him to be greedy, or even whether greediness is an unhelpful experience that represents for him an interpretation of poor self-worth (i.e. he doesn’t deserve a big cake because his mother will not love him, and as an adult, his wife will not love him if he has it) He will become aware through dialogue that explaining why he makes certain choices can avoid future misunderstandings, and stop the perpetuation of irrational decision making. He will learn that other people, including his wife, experience his behaviours in their own way, not necessarily how they were intended.

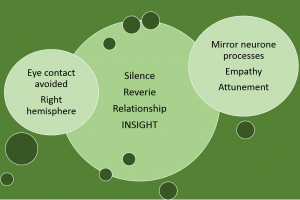

Psychotherapy and Mindfulness

Thoughts and anxiety can be inseparable. Through Mindfulness practice there can be an awareness of our thinking, noticing spiralling sequential thinking sometimes pulls us away from reality into a repetitive story of stress, and worry; Mindful practice enables us to begin to slow down fixed thinking, replacing it with flowing thoughts.

Psychotherapy acts as an adjunct helping us to notice actions and behaviours that are based on habit, or implicit memories, and previously out of our awareness. It therefore helps us to modify our behaviour and take greater control, strengthening explicit memory formation and the role of the hippocampus, enabling rationality informed by experience.

Thoughts and anxiety lose their grip on each other. Thoughts become focused based on reality, and our physical arousal is appropriate based on actual threat or excitement.

We learn to make our thoughts explicit to help identify reality from ‘make believe’. Relationships improve and anxiety decreases.

Further information about mindfulness can be found below.

If you think counselling can help you please look at my website Insightfulness or visit Counselling Directory or British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy where you might find some helpful resources.

Resources

Books

The practical neuroscience of Buddha’s Brain. By Rick Hanson, with Richard Mendius