Mindfulness for Beginners-Short Course

Mindfulness-A short Course

Mindfulness is learning to be more present in the here and now. Or conversely it is about recognising when we are caught up in our head, thoughts, perceptions or in our emotions and feelings.

When we recognise where our attention is we begin to notice the impact this has on our decision making.

Mindfulness for Beginners

The first course ran in June 2019 and the participants each had different reasons for attending; those who came knowing mindfulness was meant to be good for anxiety, and those who had been told it would be good for them and those who were just curious.

The flexible nature of the course allowed each session to evolve depending on the questions that arose, and the reactions to peoples’ experiences of meditating.

In Session One it was acknowledged that very few people had meditated before, thought of doing so was in itself a little anxiety creating. But the first step into mindfulness almost happened before we knew it. On arriving and settling onto our chairs we were encouraged to just pause and notice the thoughts and business in our heads. We were then encouraged to let these go, knowing we had chosen be in this room with these people. Session one offered insights into Mindfulness as it has developed in the Western world and also how it is part of Buddhism. There was an activity which encouraged us to notice how we respond to senses, thoughts and perceptions.

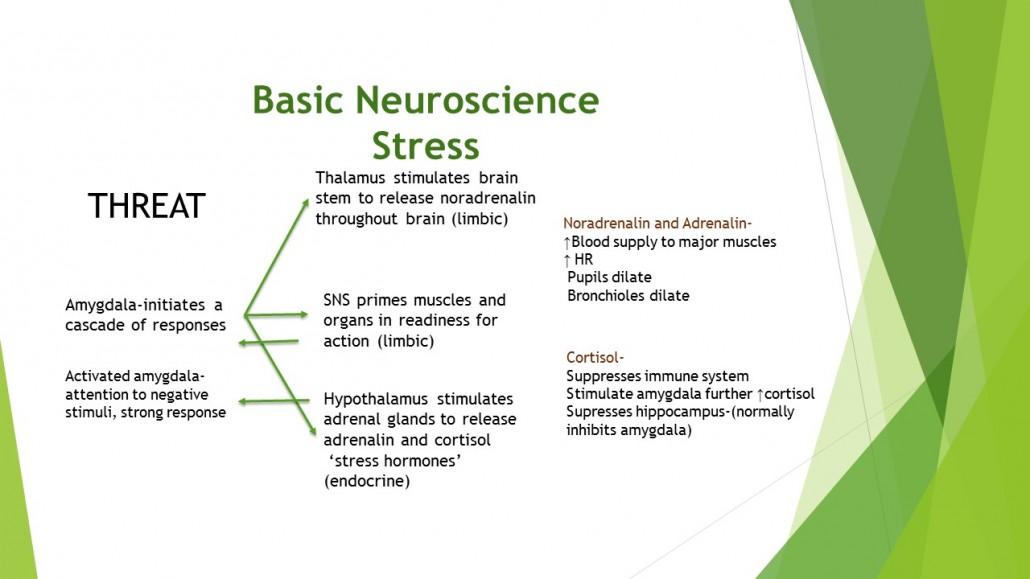

The second session was a little bit more personal. The participants had been encouraged to try meditating at home and so we could ask about the ‘apps’ available and be honest about how hard it was to find time to meditate. We were then taught a little about the biology of anxiety and that it is a normal response to danger. It was useful to notice how thoughts can cause the same anxiety response as real danger. https://www.insightfulness.co.uk/thoughts-and-anxiety/

Also in this second meeting we were encouraged to reflect on familiar habits we might have when we feel anxious or emotional. For example some people will get angry, or want to blame others whilst others can have the opposite response and feel they can never do anything right and become silent and withdrawn. There was a longer meditation.

We could make suggestions as to what to cover in the last week and people wanted to understand more about why we as humans get stressed and anxious. We learnt how thoughts, beliefs, behaviours and emotions are all inter-linked. It was also helpful to understand that our brain motivates us in different ways and sometimes we over-ride this because we think other things are more important. We work hard to get recognition and money to buy pleasurable things but this might be at the expense of being with friends and family who provide us with safety, comfort and security.

I thoroughly enjoyed leading this course and sharing my knowledge of Mindfulness.

We were provided with handouts and reference material, and told how this course is a good start before embarking on the 8-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction course.

Useful resources

Books

- Wherever you go there you are by Jon Kabat-Zin (2004)

- Mindfulness: A practical guide to finding peace in a frantic world By Mark Williams and Danny Penman (2011)

For anyone interested in the science behind mindfulness-

- The practical neuroscience of Buddha’s Brain, happiness, love and wisdom. By Rick Hanson with Richard Mendius (2009)

Websites

- Mindfulness for Mental Wellbeing http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/pages/mindfulness.aspx

- Be Mindful https://www.bemindfulonline.com/the-course/

- Oxford Mindfulness Centre http://www.oxfordmindfulness.org/train/

- Headspace https://www.headspace.com

- Rick Hanson resources https://www.rickhanson.net/

Links

https://www.insightfulness.co.uk/courses/

https://www.insightfulness.co.uk/a-mindfulness-guide-for-the-frazzled-by-ruby-wax/